In my previous article I mentioned the listening and research phase developed by Rob Knopper and Noa Kageyama’s Audition Hacker Bootcamp, which proved extremely helpful in gathering the best interpretation of each excerpt in phrasing, tempo, etc.

The next phase involves your instrument (finally!) and requires that you practice to develop muscle memory. We all know that the longer we’ve played a piece, then the easier it becomes. And sometimes when nerves strike and focus is lost, the performance is still executed well! We often wonder, “How did I do that? It felt like my fingers were magically playing the notes themselves.” In these occasions, we truly understand the importance of having deeply ingrained muscle memory as a backbone to rely on when under pressure.

So instead of starting at the beginning of your excerpt (or piece), you begin with the very last note. You practice this note until you feel that the attack, tone, and release are perfect and just the way you want, building in that muscle memory and repeating possibly 20, 30, or 40 times! Then you add the second-to-last note and play the two together. Incrementally you add one more note at a time until you’ve completed two full measures. Then you add one note at a time in the third-to-last measure to the second-to-last measure, working up to two-measure chunks, working all the way back to the beginning.

The benefit of working backwards (rather than just gradually increasing the tempo) is that all of those repetitions are built into your muscle memory at the ideal average tempo you discovered during your research for your excerpt. It can take quite a long time to complete an excerpt in this fashion, especially an excerpt with lots of sixteenth- and thirty-second notes. However, the process pays off and the muscle memory sticks. And once an entire excerpt has been treated in this method, you then maintain it with a daily run-through. If there seems to be any issue, you can then apply this method again in its entirety or where needed.

Realistically, it is not feasible to do thirty or forty repetitions when playing the flute without exhausting your embouchure, hands, and posture, so I modified it and did about 10-20 repetitions. You do not have to stay 100% focused for each repetition, however, I recommend that you maintain good posture and let any physical tension creep in. I found that I had to take frequent breaks as the length of the segments increased, since both physically and mentally it is exhausting. The process was especially helpful, though, for learning new excerpts and training the fingers to learn the patterns solidly.

RECORDING

Following the research and muscle memory phases, one begins to record. Many people do this, but this method is very methodical. To begin, record your excerpt entirely. Then listen back, take notes, and problem-solve. Distance yourself from what you just recorded and approach it as a listener. That way you can think more objectively and not take things as personally. Notate the problem and find a solution, before then returning to your performer self to try it out.

For example, you might notice that the phrase is not shaped as much as you want. Then shift to problem-solving mode and ask yourself: what can I do to make the peak of the phrase stand out? You might realize that in addition to playing the peak louder, you might add vibrato and/or color change. Then switch back to performing mode, experiment, record, and listen again.

Through this process you systematically build your interpretation. This is especially helpful with excerpts that present musical challenges and where an audition committee might be looking for artistic creativity and musicianship. I know that I developed better interpretations following such inquiry, even on excerpts I had been practicing for over a decade. It challenged me to ask myself all sorts of questions about my default interpretations: why am I emphasizing this note here? Do I want to? Does it make sense with the meter? Then when you are happy with your interpretation, you record again and compare your first recording to your last to hear your progress. It is very satisfying!

Again, this phase is very time-consuming, but helps a musician to develop his or her vision for each excerpt. It might take an hour or two, but likely this will be more well-thought out and prove convincing to your audience. Even if you don’t have an audition coming up, you can take a standard list of excerpts and apply these phases to them. While this technique is taught with orchestral excerpts, one can certainly apply it to solo and concerto repertoire.

Revised and edited by Claire Thompson, PhD.

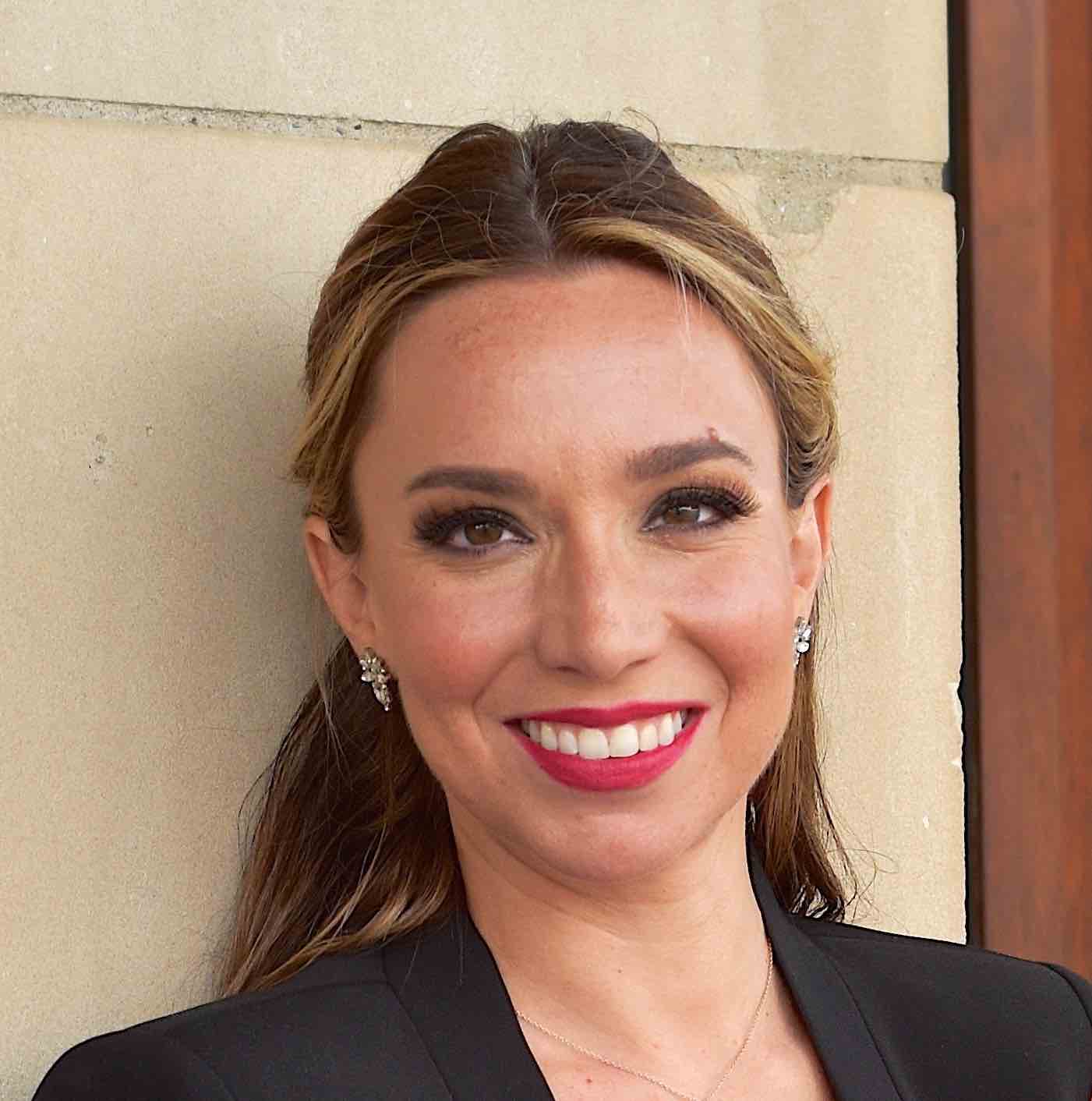

Amanda Blaikie

Amanda Blaikie is the 2nd Flute of the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Previously she was the Principal Flute with both the Michigan Opera Theatre Orchestra and the Sarasota Opera in Florida.

Amanda earned a Professional Studies Degree at the Manhattan School of Music under the tutelage of Robert Langevin. She regularly performs at the Detroit Chamber Winds & Strings, Great Lakes Chamber Music Festival, New Music Detroit, Cut-Time Players, and the WRCJ Classical Brunch Series.

Comments are closed.